The Chagos Archipelago or the ‘British Indian Ocean Territory’ are a collection of British islands and reefs in the Indian Ocean that contain a strategically vital US/UK military base. They are in the news at the moment because the British Government, on the back of a Mauritian and Chinese lobbying exercise, has decided to follow an advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and announced an offer of their sovereignty to the Mauritian Government.

This move has been heavily criticised. The descendants of the original inhabitants are heavily opposed to a deal, they wish to remain British and the hand over would see their hopes of returning to the islands gone forever. The Conservative opposition party have opposed the move as has the Reform Party, who point out that the Conservative Government was itself less than robust on the issue. The most important potential opponent of the deal is however President Elect Donald Trump who reportedly fears for the future of the base without the protection of British sovereignty over the outer islands.

So why is handing over the islands even an issue? For most countries it would not be, but the UK’s Foreign Office is not what it used to be. Arguments about keeping African opinion on side ‘soft power’ predominate over the more tangible issues of ‘hard power’ sovereignty. Some suggest the UK’s Foreign Office’s ability to defend UK interests has suffered from a consciously anti meritocratic recruitment drive combined with a merger with the far larger international aid department which in a unforeseen reverse take over had changed the focus of the FCDO into that of an aid provider.

This all led to a projection of weakness in the face of a skillful Mauritian lobbying and legal exercise organised by a number of (ironically) British lawyers. This culminated in a successful attempt to engineer an ‘advisory’ opinion from the ICJ. and a vote in the UN General Assembly – again very much non-binding. The UK in the face of this breeze bent and then fell over, before negotiating a humiliating surrender.

The Mauritian legal claim

The Mauritian claim is a curious one. The islands have undeniably been British since 1814 and were claimed from as far back as 1786. Mauritius has never had sovereignty over them. The British, in an internal British Empire re-organisation, attached the islands to the then British Mauritian colony in 1903. In 1965 Britain separated the Chagos Islands from Mauritius and incorporated them in the new colony of British Indian Ocean Territory along with islands which had previously been part of its then colony of Seychelles. Mauritius was subsequently was granted independence.

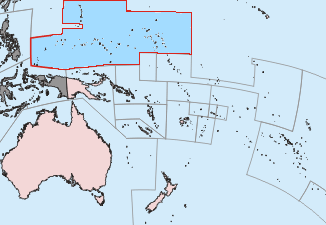

Mauritius’ claim (see right) is therefore based on the Imperial subdivisions as existed some years before independence and that the (non-independent) local Mauritian Government did not agree to the re-designation. This was the argument that the ICJ adopted in its advice.

International law is however mostly politics and the UN is awash with states willing to bang a ‘decolonisation’ drum for domestic audiences.

The implications of the ‘advisory opinion’

Now that the ICJ has given an opinion on Imperial subdivisions, it might be interesting to see where this might take us. If the British separated the Chagos from Mauritius pre independence, it is by no means the only occurrence. In fact British, French and US history is awash with changes in territorial boundaries. So here are a few states the ICJ may wish to look at following its new found precedent.

St Kitts Nevis and Anguilla

The British Territory of Anguilla was once a part of neighbouring St Kitts but was separated off prior to independence and the Anguillans wished to remain a British territory – does this mean St Kitts could now claim Anguilla? For that matter The British Virgin Islands were also administered from st Kitts.

The Cayman Islands

The Cayman Islands were at various times administered from Jamaica, which subsequently became independent – the Cayman Islands decided to remain British. Likewise the British territory of Pitcairn in the Pacific was administered from Fiji and then the Solomon islands by the High Commissioner for the Western Pacific until it was separated out. The Turks and Caicos Islands were at various times a part of the Bahamas and a dependency of Jamaica. Which claim would the ICJ entertain? As or the retained areas of British Cyprus, do we want to lose another vital military base on the back of a lobbying campaign?

The Central African Federation

Going further back in history, in the 1950 and 60s the British created a Federation of what is now Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi. This came to an end when Zambia and Malawi were separated off and granted independence. Was that lawful?

The Indian Empire

If the ICJ really wishes to tackle the issue of colonial partitions they should look at Britain’s handling of Indian Independence. For much of its history the Indian Empire was a state within a state and a very powerful one at that. Not only was the Indian Empire a large land power, it controlled its own overseas territories. At various times controlling Aden, St Helena, Burma, colonies in Malaysia and a whole range of treaties in its own right. Of course when India became independent it lost Burma, Pakistan East and West but the British held on to former Indian territories, such as Aden and Malaysia – was that lawful?

The French Empire

France although not a diplomatic supporter of the UK in the Chagos case still holds a number of its own island in the Indian Ocean, having granted independence to other parts – does the ICJ believe these are illegal?

The US territories

For that matter the US has its own overseas territories cut out of larger areas. Guam was once part of the US Trust Territory but separated out.

If the ICJ is determined to go down that rabbit hole there is no knowing where they may end up. Thankfully however France and the United States are likely to take a more robust view than our own Mandarins.

It is clear the ICJ has seriously overreached itself in a desire to play the politics of ‘decolonisation’, there can be no logic for looking at a British territory since 1814 while not opening up a whole can of historical and political worms. The UK should now recognise that fact and reaffirm its sovereignty as it has done since 1814. The UK has no need to pay the ICJ any notice. A quick recap.

- The ICJ opinion is advisory – there is no need to follow it.

- The UK did not agree to be bound by the opinion and did not request it. The UK specifically exempted the ICJ from dealing with disputes with Commonwealth states.

- The UN General Assembly resolution is also non binding (they never are) and the product of a lobbying exercise. The UK is a Security Council can give binding rulings but the UK and USA wield vetoes.

- Mauritius is not a western ally. It has links with China and its standard of government and Human Rights have been questioned. Giving Mauritius the sovereign freehold over the archipelago would inevitably endanger the base itself, both militarily and legally.

The legal status of reefs

Key to the security of the military case is the UK’s sovereignty over the surrounding sea and reefs. Putting them under Mauritian sovereignty would create a potential security danger, something that has been considered for decades.

One potential issue is the creation of a Chinese base in the area on areas the Mauritians could not defend. One such is the curious case of Blenheim Reef, an area usually submerged except at low tide. As it is not above water it is not technically land, yet is within BIOT. The UK has claimed the reef, but under Mauritian Sovereignty there is little to stop the Chinese moving in to build an artificial island as they have done in the South China Sea – endangering the security of the base. Is that a risk worth taking?

We need to accept that the Chagos case is not so much about law as clever international politics. It is the politics of law the UK should improve its mastery of. Lobbying should be matched with lobbying. UK partners and those in receipt of UK aid should not be allowed to vote against key UK interests without any diplomatic push back. We should not trade hard for soft power and should improve the quality and instincts of our diplomats. There is no reason that the Chagos Archipelago should not remain British indefinitely and that the Chagossians could be allowed to return to some of the outer islands. Let’s hope President Trump has a keener sense of British Interests than our own FCDO.

Note:

The Chagos military base features in my novel ‘The Durian Pact‘ as a vital staging post for the UK military.